On being a frequent crier

I wish I didn't well up so easily, but thank goodness for weepy artworks

Once a week, I have what I call an expensive cry. I sit for 50 minutes talking to my therapist on Zoom and make a dent in a box of tissues or, more usually, a loo roll (AKA toilet paper, although I had an editor who forbade the T-word in his newspaper for reasons, so I still feel uneasy about using it). Before the pandemic, I used to sit in a room in my therapist’s apartment and would try and get my money’s worth out of her Kleenex. Now I have to supply my own. (I know that I am extremely fortunate to be able to spend money, and time, on shoring up my mental health. I don’t take it for granted, even if I do make gentle jokes about it.) That’s far from the only time I cry, though. I cry when I’m sad, happy, proud of someone or when I’m frightened.

Crying in the club (art gallery)

I didn’t think I could recall ever crying at the sight of a painting or sculpture, which made me worry that I’m a dead-inside philistine, but then I remembered the Marina Abramović retrospective at the Royal Academy last year. Before the doorway where you had to squeeze through a naked man and woman (and decide who you wanted to face as you did so. A new awkwardness achievement unlocked!) was a long table upon which different objects were laid. This was a recreation of the Serbian artist’s performance piece Rhythm 0 (1974), which gave the following instructions:

There are 72 objects on the table that one can use on me as desired.

Performance.

I am the object...

During this period I take full responsibility.

Duration: 6 hours (8 pm – 2 am).

The objects included perfume, honey, bread, grapes, wine, scissors, a scalpel, nails, a metal bar, a gun, and a bullet. Abramović, who in the original performance stood for six hours as the audience used the items on her body, lived to tell the tale. But suffice to say that Chekhov’s Gun theory of storytelling (“one must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off. It’s wrong to make promises you don’t mean to keep.”) was very much at play as the audience brawled over whether or not to shoot her. The physical objects gave me chills when I saw them, but it was the photographs of Abramović being undressed, drawn on, wounded and abused that moved me the most. In some of the pictures you can see her eyes shining with tears as blood dries on her skin. Her vulnerability, and the horror of what humans will do to each other given the chance, made me cry.

I cried, for different reasons, watching the current advert for Battersea Dogs and Cats Home (it’s here if you’re in the mood) this week. I cried at a funeral last week. I used to cry at work when It All Got Too Much. The demands of the job, the endless diet of heartbreaking news headlines, the constant stream of information. I’ve felt shame and frustration about how readily my tears spring forth - appropriate when laying a family member to rest, less so when my face is leaking onto my computer keyboard. In fact, when I was doing research for this post, I came across a great column on crying by a preternaturally cool and elegant former colleague, much more senior than I was at the time. Jo Ellison’s take rather made me squirm to remember how regularly I sported a flushed, wet face due to workplace weeping:

“In real life, I have a very low tolerance for crying: office weeping in particular is a red flag. Rather than shedding tears as an expression of empathy and understanding, I prefer my weeping to be solitary, brisk and ideally exercised in contexts that do not affect me personally — such as while watching documentaries, Crufts, or seeing old men dine alone.”

Would that I had so much control over my tear ducts. When the rush of emotion comes, be it caused by stress, overwhelm or despair, and I feel my eyes prickling, all I can do is try and find somewhere private to ride out the waves and calm myself down. There’s plenty of research to suggest that crying makes us, ultimately, feel better, and that it helps our parasympathetic nervous system help itself, but I for one could do without the aftermath of the tell-tale pink nose, red-rimmed eyes and the feeling that I’ve made a fool of myself. It’s an emotional hangover made worse by tears being so often seen as an oversensitive, illogical and downright female overreaction.

But while some studies show that women are more likely to well up than men, crying is universal and timeless, and emotion isn’t gendered. Art is, of course, a reminder of this, holding up a mirror to all the ways that humans human. There’s the Virgin Mary’s perfect, pearlescent tears over her dead son, delicately painted by Titian half a millennia ago, and Roy Lichtenstein’s bold, brittle Crying Girls (1963-4), their sadness broadcast in acid yellow, dull green, purplish-blue, and Life Magazine red.

Then there are the tears of Sam Taylor-Wood’s Crying Men (2002-4). A throwaway comment at a dinner party - “women cry and men get angry” - is said to be the inspiration for her photographs of thesps in floods taken in the early Noughties. Partly because of the recognisable subjects, but also due to the staging and lighting of each shot, these images feel slickly cinematic rather than grittily real, but some of them tug at my heartstrings nonetheless.

As a frequent crier, it’s hard not to wonder whether Dora Maar’s distress as depicted in Weeping Woman (1937) was caused by the painting’s creator. It’s tempting to read into the horrified tears of the maid servant in Artemisia Gentileschi’s Cleopatra (1633-5) some of the gruelling emotions that the artist experienced in her own life.

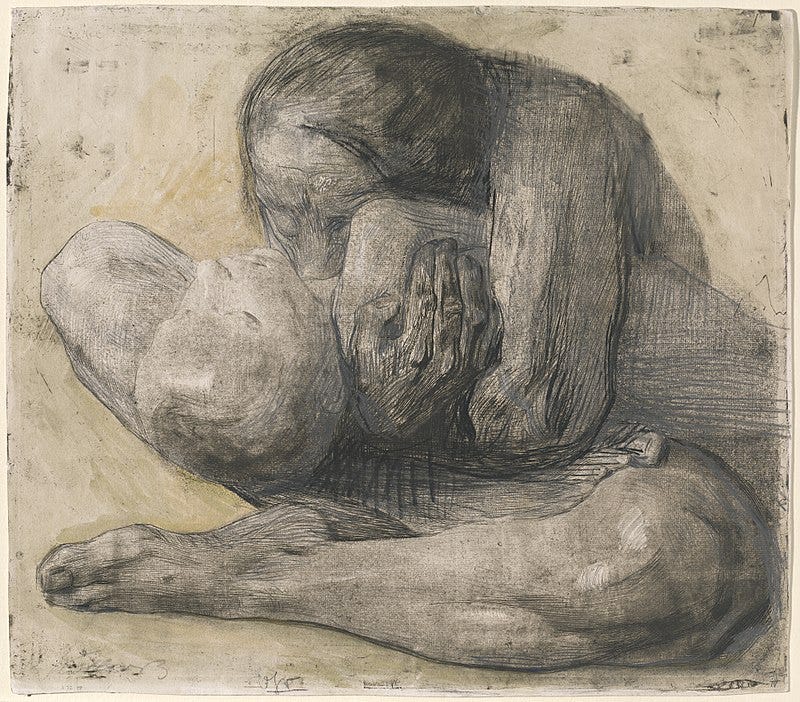

I think that if I were to see Käthe Kollwitz’s etching Woman With Dead Child (1903) in person, I would be brought to tears by the raw grief that is present in every line of the mother’s hunched and desperate body. I haven’t experienced the death of a child, but I have howled out a different loss, so I can at least recognise the agony brought out into the open in this work. There are no visible tears, but the abject sorrow leaks out nonetheless. The model for the child in the etching was Kollwitz’s youngest son, Peter, who was seven at the time. In 1966, her elder son Hans wrote about this artwork, and another, with a similar theme, titled Pietà.

“I asked mother where she got the image of the mother with her dead child from – years before the war – which featured in almost all her pictures from that period. She thought she foresaw Peter’s death even then. She said she had been crying while working on these images.”

Peter died in October 1918 in Flanders Fields.

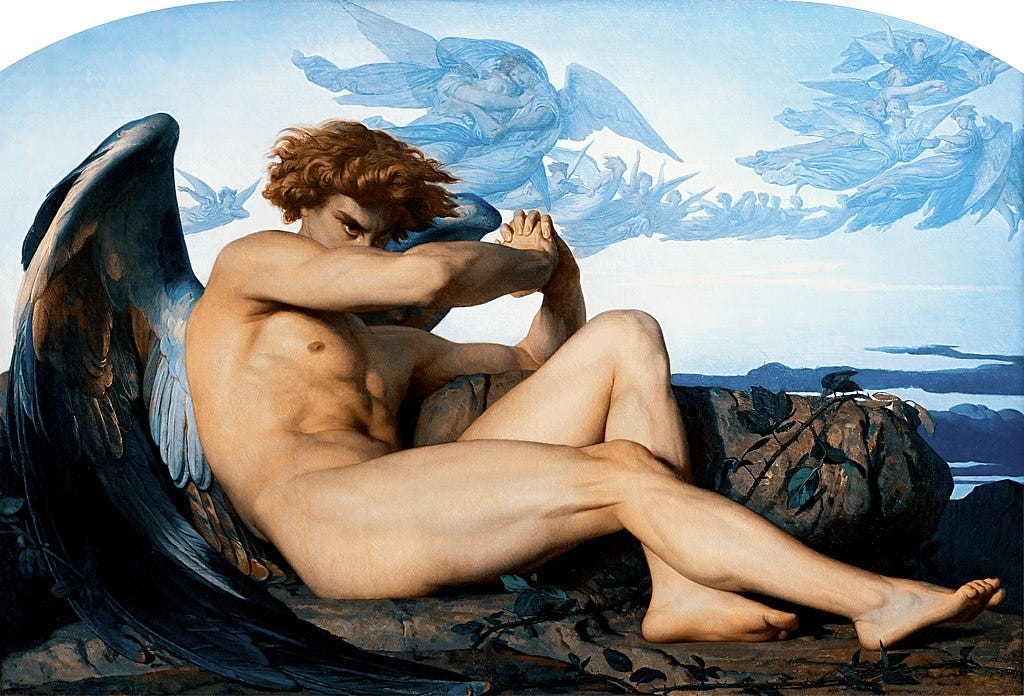

In the face of Kollowitz’s foreshadowing of her future grief, I hope it’s not too crass to move on to the sparkling tears of a sulking Lucifer in Alexandre Cabanel’s rather sexy The Fallen Angel (1847). He looks more furious than melancholy, a bad boy who’s been found out. I wonder if it’s wise to feel any sympathy at all for the devil - and whether Cabanel ever had a raging, thwarted sob when found to be in the wrong. Still, if the dark lord has times when he has to have a good cry, I’ll take that as a win for my own emotionally leaky team.

I love the weird glamour of Detroit-based artist Laura Kalman’s work, her use of the body and unexpected materials that engage with it. Her Flourish series (2016) features “decorative swoops [that] are constructed into gold-plated sculptures that interact with the body referencing bodily fluids expelled during states of repulsion, pain, and joy.” Cry me a river of golden tears. Pieces in her Hard Wear (2006-9) and Devices for filling a void collections also suggest, to me, a kind of material memorialising of tears so that they last rather than being wiped away.

And yet, for all my championing of the right to cry, for all these artworks that confirm that weeping is the most natural thing in the world, I caught myself out when I was newly at art college. When a fellow student was tumbling into tears, pacing and stressed about the questions a tutor was asking about their work while a group of us looked on, I mentally rolled my eyes. For goodness’ sake, I thought. What’s the big deal? These young people are so delicate. Tsk tsk.

The following week, I found myself bolting from a life-drawing class for a cry. In the grand scheme of things, it was a tiny bit of discomfort that somehow made me crumble. I’d felt increasingly overwhelmed by what I couldn’t do, and made the mistake of looking at everybody else’s work. Mine was rubbish in comparison, therefore I was rubbish. I felt hot, trapped and useless and ridiculous for getting teary about it. A friend tried to help, whispering suggestions about basic anatomy, but by the time the drawing tutor came over, I realised I wouldn’t be able to speak to him without sobbing. I ran off, and hid as I let myself cry my not-good-enough out. My friend found me (it wasn’t a very good hiding place) and calmed me down. I didn’t go back until the next day, when I apologised to the tutor and explained why I’d scarpered.

I then sought out the student who’d had the hard time a week before. I told her that I’d realised exactly how she’d felt when she was under scrutiny and buckling. That I hadn’t been very sympathetic then, that I was sorry, but that I got it now. Trying to do new things makes us vulnerable, and caring about them opens us up to a lot of emotions, which is a good thing. And while I’d love to have dry eyes and a poker face under pressure, as Elizabeth Gilbert puts it so brilliantly, I have the opposite: miniature-golf face. And it seems like that miniature-golf course has a LOT of water features.

Loved this. I cry ALL THE TIME.

This is an education. I’m always embarrassed by the opposite situation: I’m just not a crier. I can only really cry if other people are crying - it’s a mirror response. I have never, ever cried in therapy because my therapist isn’t crying, so I just can’t. I’ve been called out on this by several therapists but they have to go first!