'I could clean, but it would be a terrible effort'

The artists who make me feel better about living in a mess

I’m writing this when I could be cleaning the kitchen floor, which is making me want to weep with its tea-bag drips and its seeded sourdough crumbs in the corners, but not so much that I actually want to sort it out. Other rooms in the flat also showcase my house-keeping fails, from smeared mirrors to taps that are reptilian with limescale. I find that I can only motivate myself to clear up when one of three things happen. One, when there’s a guest coming, and my shame at the mess overrides my shame at not knowing how to properly clean and organise things. Two, when there’s something even worse that I should be doing - the reprehensible state of the skirting boards becomes suddenly pressing when the alternative is tackling an Alpine range of paperwork. Three, when the despair of cosplaying Miss Havisham 2.0 finally becomes too great and I finally stir myself to Do Something About It.

Cleaning is a killer as it’s both boring and stressful. I will happily sink into the sofa for hours watching Reels of people doing extreme housework - my current favourite is @cleanwithbeax and her videos of sorting out a gruesome rental flat - but on the rare occasions that I do something about my own home, I quickly get overwhelmed by the task. I clean. I fall down a wormhole of all the places I’d never even thought about before that are gathering tumbleweeds of fluff and dust and or collecting kitchen grease. The previously unimagined vistas of the underside of kitchen cupboards, or the the back of my front door.

I then look at the even-mightier works that seem utterly impossible (removing the blackened horror sealant round the bath and replacing it; defrosting the glacial tomb of the freezer and buying it new drawers) and despair.

“Just set a timer for 10 minutes and see what you can do!” trill the web articles that claim they’re going to help me achieve domestic serenity. “I put the radio on and zone out while I do the ironing. It’s strangely soothing,” people claim on Instagram. But… irons are for dress making and setting fabric paint, no? What other function could they possibly serve?

True, when I have been desperate enough to follow the Pomodoro Technique, when the threat of a visitor has forced my hand and the flat is, briefly, free of the piles of stuff that usually litter every flat surface, when everything is wiped and dusted and polished, there may be a brief, exhausted sense of satisfaction. I fleetingly feel like a proper adult human, and have a touch of pride knowing that if I died suddenly, right now, and loved-ones came to go through my personal effects, they wouldn’t find a hoarder’s nest worthy of a TV show. But the thing about cleaning is that it is never done. You can never truly cross anything off the list, because a few days, or a week later, the bastard thing needs wiping, dusting, polishing or defluffing again. UGH. The tyranny of dust has enslaved countless generations of women and I for one want to revolt.

I have learnt how to properly clean the kitchen sink, which only came about when I realised I was so frightened of what lay beneath the washing-up bowl I was avoiding going near it, and that I didn’t actually know how to clean a sink beyond spraying it with some bleachy kitchen stuff and giving it a wipe. It’s nice not to be scared of the lurking horrors every time I fill the kettle. I’ve learnt that buying new cleaning sponges or detergents can sometimes give me enough of a dopamine boost to get me going.

But I’ve also learnt that there are just so many things I want to do that aren’t cleaning, because cleaning takes so much time, precious, slippery, running-through-your-fingers time, when I could be reading about American butter sculpting in the late 19th century. Or doing shibori dyeing workshops, or getting better at making faces from air-dry clay. Or earning some money.

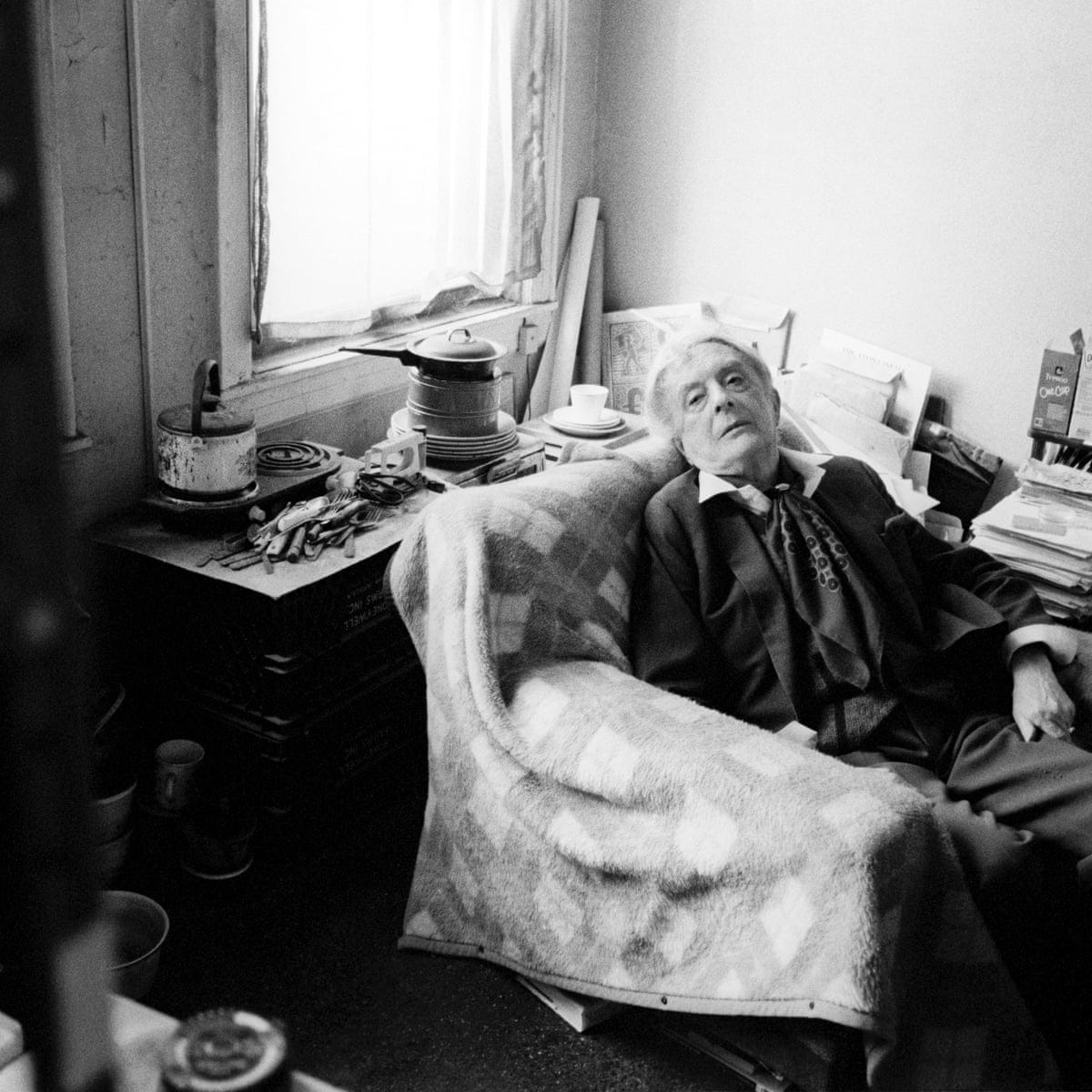

Thank God, then, for the people for whom clean and tidy living quarters are sacrificed on the altar of art. I delight when I find a new example of a creative person who clearly couldn’t give a hoot about rusting radiators or greasy splashbacks. The oft-quoted patron saint of domestic misrule is of course Quentin Crisp, whose famous bon mot (“there is no need to do any housework at all. After the first four years the dirt doesn't get any worse”) I’m tempted to trace in the dust on the bathroom lino. In a New York Times article in 1997, the late eccentric, writer and actor (indeed, the eccentric writer and actor) horrified his interviewer with the state of his room.

“There is no earthly excuse for the filth here. Lush, degenerate, I'll-never-clean-my-room-again filth,” wrote a clearly queasy Alex Witchel. “The potato peeler is rusted orange. The towels near the sink are blackened, and a corroded pot on the windowsill holds water covered with film. Everything in the small room from the bed to the single chair to the dresser seems cloaked in a soft layer of grime; even the green blanket's dust balls have gone black.” Quentin, we’re told, sighs. “'I could clean the place, but it would be a terrible effort.'' I already feel so much better about my kitchen.

On a day out in Dublin some years back I visited the Hugh Lane Gallery. It houses Francis Bacon’s studio, which was painstakingly dismantled from its original location in London and rebuilt in all its grimy splendour. The absolute state of it makes my heart sing. The feet-deep scrumpled newspaper on the floor and the coiled and crusty tubes of oil paint show exquisite disregard for the norms of tidiness and good order. The smears of heavily pigmented colour across the walls speak of the wild fervour in which they were applied.

The gallery’s website describes some of the process of recreating the space (there’s more information available when you visit): “A team of conservators, curators, and archaeologists… [carried out]... the move. The archaeologists made survey and elevation drawings of the small studio, mapping out the spaces and locations of all the objects, while the conservators prepared the works for travel and curators tagged and packed each of the items, including the dust.” For once, the thought of dust brings me joy. Piles of rags clot the surfaces, layered with paper, magazines, dirty brushes and cardboard. A mirror so foxed that it looks like it’s been shagging in the garden and eating from the bins dimly reflects the chaos.

Apparently the dedicated team shifted 7,000 objects from a space that measured 4x6 metres (there’s more on the logistics here) and the whole shebang was written off by some as “preserving a heap of detritus”, according to Hugh Lane Gallery’s Barbara Dawson. I couldn’t be more glad that this mountain of genius art shite has been saved to show how creativity can flourish in chaos, and that life is too short not to get paint on the walls.

I’m even happier when I see the working and living spaces of women artists who perhaps had more to lose by turning their backs on societal expectations around mess (although those societal expectations would likely describe it as squalor or slatternliness). Researching Louise Bourgeois for an essay, I was sidetracked by the glorious fact that after her husband’s death in 1973, she ripped out the stove from the kitchen in their family home in New York, replaced it with a hotplate, and chopped the dining table in half to use as a desk. She scrawled phone numbers and notes-to-self on the walls.

Given that she was a great hold-onto-er, keeping bills from her first apartment in Paris, it’s all the more exhilarating to imagine her getting rid of the oven: I won’t be needing that where I’m going, I can picture her thinking, as she proceeded to turn the rest of the townhouse into a studio before continuing on to art-colossus stature. Yes, her house had an “atmosphere of bohemian dilapidation” (The New York Times, describing her home after her death) and it was a “place [that] is in no shape to be seen by anyone other than its owner”. Sod that - her child-rearing, husband-having years were over and it was a place for making her work and entertaining acolytes. It sounds like it was in exactly the shape it needed to be. I can’t imagine her worrying about scattering a few crumbs.

The British painter Rose Wylie is another poster person for magnificent disregard for tidiness, in her home studio at least. I recently watched a video of her giving someone from the Serpentine gallery a tour of her workspace. She gleefully points to “evidence” of scarlet paint splodged on the stairs as she ascends to the room where she paints. And what a room! A palimpsest of newspaper upon newspaper (to keep the “planks” nice, she says, and she likes a “nice build up” of paper on the floor), tables used as palettes, open paint pots littering the floor and drips and splashes everywhere. Her source drawings are sprinkled across the room, there’s scrawls on the walls, as well as her giant canvases.

There are mounds of screwed up paper that I think are piled on chairs, but as there is no visible evidence of any chair-like structures, I can only guess. In an interview with W Magazine, she expands on her philosophy. “I don’t want to be caught up in the idea that you must tidy up, which is what you get as a child: ‘Clear the cupboard, clean your paintbox, your drawers are a mess.’ When my paint tin is empty, I just throw it on the pile. Sometimes, if you have a very clean, sterile working situation, it takes time to keep it like that, and when you come in you don’t start messing it up. For me, the paints are already out. I can come in and just start working.”

When I was nervously circling my art materials after years away, I found that one way to beat the fear of being rubbish was to always have things to hand so that it became second nature to draw while eating my breakfast, or add a few blobs to something I was painting. It felt increasingly natural and right to reach out and find tools immediately and then just bloody use them. It did nothing for the sense of order in my flat but a lot to help me feel I had a right to create.

I was talking to one of my fantastic tutors, the sculptor Frances Richardson, about artists and mess. She told me a little about how she works in her studio, and it really resonated with me. “I like living with a bit of peril, objects piled on top of each other, activated. I had a huge pot of paint balanced on a chair to do tiny touch ups on my workbench. Of course I spilt it, but I like living on the edge.” I think that I do, too.

''Of course,’ said Quentin Crisp, “you'd have to live alone to live as I live.'' The thing is, I didn’t always live alone, there used to be another person, and we also had a cleaner. But circumstances change, and with no one now to tell me off, no cleaner to tidy up for, I muddle along in my mess, making my art. I am beyond lucky to have somewhere to live and work that I can, for now, afford. When I leave a half-started oil painting on its easel for months, when the kitchen table resembles a lasagne of sketch books, coloured pencils, broken jewellery and different types of glue, I feel relieved to my bones than I am not rearing a child in this stuff-studded flat, I am looking after a baby artist. I can see myself as eccentric rather than neglectful, and I can get on with the interesting business of living rather than cleaning the damn floor. As the Dutch artist Marlene Dumas puts it in Women and Painting, “I paint because I am a dirty woman/(Painting is a messy business).”

There’s something about artists’ mess that’s so appealing. It has a different timbre to everyday mess (cf. I discovered this week that my som was shoving used tissues between the books on my bookcase; this is not the elegant kind of mess). For me, the question is, do I clean, or do I write? Writing always wins.

Love this. I am raising a child in mess and often feel a deep sense of maternal shame for doing so (my mum is very house proud). But I have decided that she needs a role model in having a mother who would sooner prioritize living over cleaning. Life truly is too short.